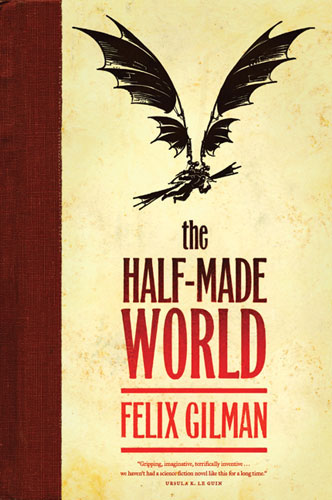

Wikipedia gives an exceedingly expansive definition of the weird western as “any western blended with another genre.” This seems rather too expansive, as I don’t think anyone would classify Blazing Saddles or Brokeback Mountain as weird westerns, despite a blending of western with comedy and romance, respectively. I prefer a more stringent line of demarcation: Weird West is the western merged with the fantastic, either science fiction, fantasy, or horror, with a dark tone to it. When it treads into SF ground, it often utilizes a steampunk aesthetic. These are not necessarily interchangeable terms, though: not all steampunk set in America can be considered weird western: neither The Amazing Screw-on Head nor Boneshaker would be considered a western. Felix Gilman’s Half-Made World, on the other hand, is pure weird western, with a whole lot of steampunk thrown into the mix.

Half-Made World has got all the elements of the steampunk aesthetic. Technofantasy? How about the spiritual brother of Roland of Gilead, who doesn’t shoot with his eye, mind, or heart, but with a revolver housing a demon in addition to six bullets: “The weapon—the Gun—the temple of metal and wood and deadly powder that housed his master’s spirit—sat on the floor by the bed and throbbed with darkness.” (39) The Gun and its demon provide this gunslinger, Creedmoor, with Wolverine-like healing abilities, preternatural senses, and Matrix-fast, bullet-time reflexes. Without it, he is only an old man. With it, he is one of many Agents of the Gun, in the service of the spirits of the Gun. Gilman is unclear about the motivations behind the Gun’s machinations, keeping the cabal of spirits outside the frame of action in a “Lodge” that made me think immediately of Twin Peaks, the Black Lodge, and the strangeness therein. The opponents of the Gun are the Line, and they too have powerful spirits inhabiting technology, thirty-eight immortal Engines who are viewed as Gods by members of the Line.

That’s the weird in this western, insofar as the Encyclopedia of Fantasy defines weird fiction as, “fantasy, supernatural fiction, and horror tales embodying transgressive material…where subject matters like occultism or satanism may be central, and doppelgangers thrive.” But this in and of itself is only weird, not steampunk, per se. For that, we need to add some Neo-Victorianism and some retrofuturism.

The retrofuturism of Gilman’s fully secondary world is the purview of The Line, the enemy of the Gun. The world of the Line is introduced to the reader through Sub-Invilgator (Third) Lowry, who is literally a cog in the great machine. He works in a small office, a “tangle of pipes and cables” poking through the walls (41), a job which “occupied a position somewhere in the middle range of the upper reaches of the Angelus Station’s several hundred thousand personnel… a hierarchy that was almost as complex and convoluted as the Station’s plumbing.” The Angelus Station, located in the city of Gloriana, is the first major destination of the novel’s heroine, Dr. Lyvset Alverhuysen, or “Liv” as she is most often called. Liv sees Gloriana through eyes alien to the world of the Line: a nightmare sprawl of “shafts and towers” that suggest a “vast indifference to the natural world.” (107) Liv provides the middle ground between the Gun and the Line, indifferent to the agendas of both, on a journey to a dubious house of healing on the “farthest western edge of the world.” (24)

The Neo-Victorianism, the way in which the book evokes the nineteenth century, is simple: the setting is a fully secondary world with a strong foundation in the American frontier. Despite the advanced technology of the Line and the metaphysical powers housed in Guns and Engines, this is a fantasy based in the nineteenth century history of the United States.

What was particularly noteworthy to me as a Lit scholar was how Gilman presented the technology of the Line, specifically in the train: “The Line reduced the world to nothing” (121), and a few pages later, “The Engine obliterated space, blurred solid earth into a thin unearthly haze, through which it passed with hideous sea-monster grace.” (127) These words echo those of journalist Sydney Smith regarding the coming of steam power: “everything is near, everything is immediate—time, distance, and delay are abolished.”

I teach two poems on the steam train every year in my introductory English courses: “To a Locomotive in Winter” by Walt Whitman, and “I Like to See it Lap the Miles” by Emily Dickinson. Students compare and contrast the poems in light of two articles: “Walt Whitman and the Locomotive” by G. Ferris Cronkhite and “Emily Dickinson’s Train: ‘Iron Horse’ or ‘Rough Beast’?” by Patrick F. O’Connell. In these articles, Whitman and Dickinson are read as deifying the train: Whitman as worshiper, Dickinson as heretic reprobate of the rails. Whitman’s poem is akin to a hymn, praising the steam engine’s “ponderous side-bars” and “knitted frame,” “steadily careering” through winter storms, unhindered by nature’s worst: a force of nature itself. Dickinson’s enigmatic verse likewise highlights the power of the locomotive, but as a force of destruction. She writes with irony in the words, “I like to see it lap the miles / And lick the valleys up.” The locomotive, like some giant monster, is consuming the landscape, not merely traveling through it. O’Connell sees the final lines as references to Christ’s advent, and suggests Dickinson is painting the train as a “fraudulent divinity.”

Gilman’s Half-Made World could easily act as an intertext to these poems, with the contrasting views of the Gun and the Line. The Agents of the Gun are Dickinson, opposed to the industrial sprawl of the Line. When Gilman first introduces Creedmoor, the Agent of the Gun is reflecting upon the impact the Line has made on nature: “Now, to his great annoyance, the hills were being flattened and built over by the Line—farms replaced by factories, forests stripped, hills mined and quarried to feed the insatiable holy hunger of the Engines.” (33)

By contrast, the Line could be considered analogous to Whitman, made up of servants like Lowry, who experiences the mysterium tremendum—literally, a holy terror—of Rudolph Otto’s The Idea of the Holy in the presence of an Engine: “And the thing itself waited on the Concourse below, its metal flanks steaming, cooling, emitting a low hum of awareness that made Lowry’s legs tremble.” (44) Lowry contrasts landscape “properly shaped by industry” with the “formless land, waiting to be built” (71), recalling the devastation of the American countryside in Dickinson, where the locomotive can “pare,” or split a quarry without effort. The spread of industry changes the face of the world; wherever the Line goes, it seeks to tame the “panoramas” of the unsettled West, a place of “Geography run wild and mad.” (25) Elsewhere we read that “the Line covers half the World.” (37) And though we are provided Lowry’s perspective, The Half-Made World is clear in demarcating the lines of good and evil: while the Gun is bad, the Line is worse. Steampunk technology is not rendered with the romanticism of Girl Genius here: the machines of the Line “bleed smoke” and “score black lines across the sky.” (35) Industrial technology is blight, not blessing, in this alternate world.

When I began my study of steampunk by reading Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day, I wondered if its theme of the loss of frontier, of unexplored and untamed spaces, was also a theme evoked by the steampunk aesthetic. It’s clearly a major theme in The Half-Made World, which Gilman explores with a page-turning narrative, engagingly complex characters, and deftly descriptive prose. Thankfully, it’s the first in a series, resolving many conflicts while leaving the requisite loose threads to entice anticipation for subsequent installments. While it’s not for those who like their steampunk in an upbeat utopia, The Half-Made World is custom-made for those looking for a dark dystopia filled with weird west, gritty steampunk, and literary intertexts.

Read an excerpt from The Half-Made World here on Tor.com.

Mike Perschon is a hypercreative scholar, musician, writer, and artist, a doctoral student at the University of Alberta, and on the English faculty at Grant MacEwan University.